In contrast to our illustration, which may seem sarcastic in view of climate change, production cells refer to a type of manufacturing in which different machines or workplaces are usually grouped together locally. This allows similar work on several different products to be concentrated in one area, ideally producing functionally self-contained outputs (intermediate products, assemblies). This is particularly advantageous for series production with a large number of variants. Typical implementations of this include assembling cells or so-called flexible manufacturing cells (mechanical production).

History of the production cell

Since the 1920s, when Henry Ford’s assembly line manufacturing opened up an extensive customer base for mass production, the assembly line has gained enormous importance in industrial production. For products with largely identical parts in large quantities, there is practically no more efficient use of production resources than in assembly-line production. Short lead times and the continuous demand for materials within the same cycle time also reduce expenses in control and logistics.

Starting in the 1970s, people’s needs changed and individual products became more in demand. However, the price expectations of the market were characterized by mass production. Automation technology was still relatively in its infancy, so new approaches to work organization were sought. The idea of the production cell was born. The Swedish carmaker VOLVO, which began to establish this type of manufacturing in 1972 as a replacement for the assembly line, is often cited as an example.

The employees working in assembly lines at the time also had high expectations of this new type of work system. This was because the high efficiency of assembly-line production was countered by disadvantages with regard to the personality development of work in clocked assembly lines. Monotony and time constraints were also blamed for high sickness rates in the corresponding production lines.

The view of work science on cellular manufacturing

The Taylorist principle, which is often referred to as the organization of work according to type with low activity scopes in flow production, has given rise to some controversial discussions, not least in the field of work science. In this context, work enlargement and work enrichment became established as organizational principles. They attribute a stable high level of work motivation to an optimal variety of physical and mental demands on the employees.

This is implemented by temporal decoupling of work steps for each individual employee through buffers. These buffers are designed so that each resource in the manufacturing cell has a supply of work at all times, which can be tapped flexibly in contrast to assembly-line production. The low time commitment to a cycle time that can be achieved in this way is considered by work scientists to be a relevant advantage over assembly line production.

Attempts are being made to reduce the complexity of the control system by means of simple mechanisms that have been tried and tested in lean production (e.g. KANBAN, ANDON, POKA YOKE) so that employees can act autonomously in the cellular layout. In this context, the terms (semi-autonomous) group work or group production are often used.

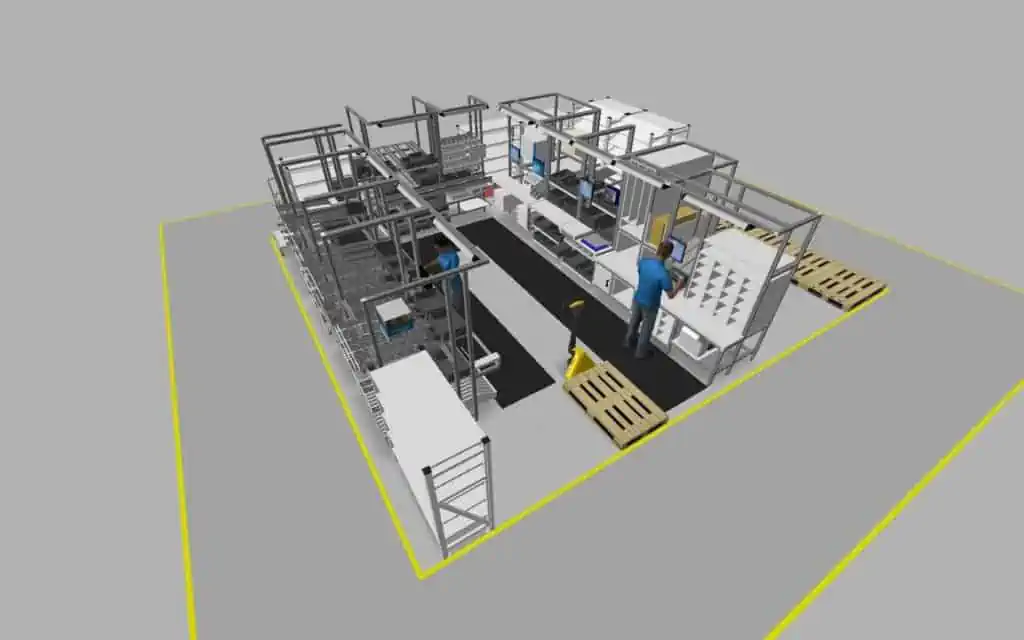

The design of production cells

Compared to line production, the material flow to and in a manufacturing cell allows more degrees of freedom. On the one hand, strict sequencing is not required, and on the other hand, more material tends to circulate due to the necessary buffering.

The principle of line production in one-piece flow is generally used within the production cell; larger transport lots can be realized between the individual manufacturing cells (e.g. by means of tugger trains). The same applies to components, assemblies, standard parts, and small parts.

As a rule, production cells transfer the output to several different downstream processes (further processing or intermediate storage). Thus, cellular manufacturing regularly creates a networked structure of the manufacturing process, which is visible in the block layout. The design focus in cell production thus shifts somewhat more to the production layout than to the cycle timing, which is the central design task in line production::

- Inside the production cell, a value-added-centered arrangement of machines and stations in the flow is considered ideal; a typical shape is the U-layout.

- The position of the manufacturing cells in the production layout is determined by their material flow among each other and their supply intensity from storage areas. Close interlinking, as in line production, is only necessary for large, multi-step production processes (e.g. in automotive manufacturing).

Conclusion

Cell production combines the advantages of the production line and job shop production by using the flow principle internally and the shop floor principle to arrange the cells in relation to each other. By exchanging, adding, or removing individual manufacturing cells, the production capacity can also be easily scaled. As a result, this type of organization achieves high flexibility combined with good adaptability and demanding work tasks.

Related topics: